- Las Positas College

- Reading & Writing Center

- Reading Strategies

Reading & Writing Center

Reading for Review

There are many times when you will need to review what you've already read so you are prepared for the next step, such as before a big test or right before you begin writing an essay. Some of these strategies can be used before, during, or after you read, but most will help you go back after you've read so you can recall main points and details.

These strategies are especially helpful if your purpose is...

- To study for an upcoming quiz that is based on a reading

- To prepare for an in-class presentation or discussion founded on research or reading you've done

- To study for a mid-term test or a final exam

- To write an essay or in-class paper

Here are some reading strategies to help you review:

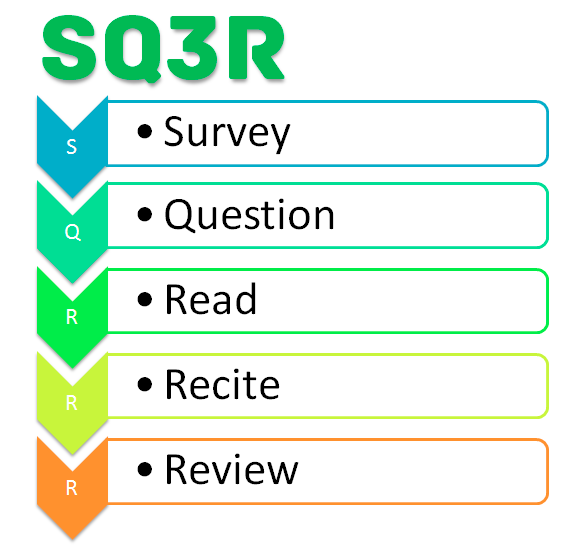

SQ3R: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review

RECh: Read, Explain, Check Your Understanding

Paint a Picture in Your Mind: Diagramming a Text

SQ3R: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review

S = Survey

Flip through the chapter or scan the article. Look for natural breaks like paragraphs or subsections that might have their own subheadings. If there are no subheadings or logical divisions, spend some time reading the first sentence of each paragraph. This will give you an overview of the text.

Spend about 5% of your time on this step.

Q = Question

When you read each chapter heading or each article subheading, turn that statement into a question. Turning a statement into a question gives focus to your reading and serves as a guide. When formulating your question, use terms such as who, what, where, when, why, how, compare, contrast, describe, explain, list, and trace. Write the question in the margin of your textbook or article. Spend about 10% of your time on this step.

Below are some examples of textbook headings turned into questions:

Textbook Subheading |

SQ3R Question |

| American History: The End of the First Party System | What were the circumstances surrounding the collapse of the First Party System? |

|

American Government: The Job of the President |

What are the duties of the President of the United States? |

R = Read

Step three requires that the reader actively participate in the learning process. Read the section with the intent of finding the answer to your question. Highlight the answers to these questions, along with any key points, examples and definitions. Spend about 20% of your time on this step.

Book |

SQ3R Question |

| Text Title: Introduction to Computers; Chapter Subheading: Types of Information Systems | What does the term "information system" mean and what are the different classifications of information systems? |

Your Turn

Below is a paragraph from a text on this topic. See if you can find the answers to the question above:

“An information system is a collection of hardware, software, data, people, and procedures that are designed to generate information that supports the day-to-day, short range, and long-range activities of users in an organization. Information systems generally are classified into five categories: office information systems, transaction processing systems, management information systems, decision support systems, and expert systems. The following sections present each of these information systems.”

(Excerpt taken from "Discovering Computers 2001, Concepts for a Connected World," by Shelly, Cashman, and Vermaat, 2000)

R = Recite

After reading and highlighting a section of the text, recite the answers to your questions out loud. Are you able to answer in your own words? If not, re-read the section again and formulate another response to the question. You may want to revise your question, now that you are more familiar with the topic. Spend about 60% of your time on this step.

R = Review

After reading the whole assignment, revisit the chapter review questions as well as your SQ3R questions and answers. Re-read highlighted textbook material. Spend about 5% of your time on this step.

Some information adapted from Brookhaven College’s “The SQ3R Textbook Studying Method”

RECh: Read, Explain, Check Your Understanding (Group Reading Strategy)

Read

With a partner or in small groups, read a single paragraph or a short section of your text. If the material is dense or difficult, choose a single sentence or even a single phrase.

Explain

When all of your group members are done reading the passage, one person should explain the text in his or her own words (paraphrase). Attempt to do so without looking back at the text. (Note: This is also a great strategy when you are paraphrasing from outside resources for your own writing.)

Check Your Understanding

Discuss the following with your partners: Were all of the important ideas covered? Was something added that was not in the passage? Does anyone interpret the material differently? If so, look back at the text to find support for the various explanations. Point to reading tools that help you decipher the text, such as defining vocabulary, using context from surrounding passages, and breaking the information down into smaller chunks. Continue to the next sentence or passage and choose a new group member to explain.

Adapted from Las Positas College’s “Reading Strategies Student Handouts English 104-105”

Paint a Picture in Your Mind: Diagramming a Text

It’s been said that a picture is worth a thousand words. However, words and pictures are inextricably linked because words can paint a picture in a reader’s mind nearly as well as paint from a paintbrush can. With this strategy, you’ll learn how to create a visual representation of what you read.

Step 1: Read the text quickly, pen in hand

Take notes as you read. Refer to a handout on note-taking or think back on your prior knowledge of annotating a text.

Step 2: Identify the thesis of the text

First, find the main point or the thesis of the text you’re reading.

Where might the thesis be located? With non-fiction, such as news articles, scientific journal articles, and so on, it’s important to know what the author is arguing or what his or her main point is. To find the thesis, you most likely will look near the beginning of the text; however, most non-fiction texts don’t begin with the thesis in the first sentence. Most texts offer the reader a hook or an attention getter of some kind and then lead into the thesis statement. Some writers save the thesis for later in the text after they’ve sufficiently piqued the reader’s attention. And, in spite of what you might’ve been taught when you were a younger student, the thesis statement doesn’t have to be only one statement; it can be many sentences combined to build to a main point. In fiction, it’s possible the author does not have a thesis because fiction focuses more on scenes and episodes rather than arguments. But it’s still possible that a fictional text might contain a thesis—it just might be implied instead of explicitly stated. In a novel, you might look for the main idea of a scene in the dialogue between characters or in the narrative provided by the author. The narrative’s intention is to offer perspective and build the storyline, and it’s in that section of the text you might find the thesis.

What is the thesis? The thesis is the main point, the primary argument, and that which the author wishes to convince the reader of. If the thesis were a mathematical equation, it might look like this: Thesis = Topic + Main Point. Another equation might be: Thesis = What? + So What? Sometimes an author’s main point is simply to inform; other times she might want to persuade the reader.

See if you can identify the thesis statement in the passage below:

On a sunny afternoon, when deliveries at his Domino’s job got slow, Delonte Wilkins sat in his old white Chevy and thought of home. Not the place he lives now—a drab apartment block on a dead-end street behind a highway in Capitol Heights, Md., which he habitually refers to as “out there”—but rather the block where he grew up in the 1990s: a strip of stately turn-of-the-century Victorian rowhouses in the Bloomingdale neighborhood of Northwest Washington.

Back then, he couldn’t have imagined that he and his friends would eventually be traveling across state lines to hang out there. That they’d draw looks and “can I help you?”s and sometimes calls to the cops. That most of them would be living in Prince George’s County, where neighbors didn’t talk and apartments were hidden behind big thoroughfares and it just didn’t feel like the kind of place where you’d meet your friends. That their former houses would be selling for seven figures—and that their new neighborhoods would be the emerging epicenters of poverty in the Washington region.

Nobody imagined it, really. Certainly not the original suburbanites, the mostly white pilgrims who fled cities nationwide for peace, safety, space—and sometimes to get away from people who didn’t look like them. Not the federal government, which declared war on poverty in the 1960s but got stuck on an old version of the fight, still targeting low-income clusters in urban centers today rather than the diffusion of people who can no longer afford to live near their work. Not the nonprofit organizations that help low-income populations, which began in the so-called inner city and are largely still there, spending far more money per urban poor person than per suburbanite in need—10 times as much in the D.C. region.

Nevertheless, nationwide, there are millions of people like Wilkins and thousands

of towns like Capitol Heights. Low-income residents are disappearing from downtowns

and becoming increasingly hidden from public view, scattered around the periphery

of major metropolitan areas. And they’re growing ever more isolated from the government

offices, social services, and networks of friends and relatives on which they once

relied....

(Excerpt taken from Washingtonpost.com, “Poverty is moving to the suburbs. The war on poverty hasn’t followed.,” by Aaron Wiener, April 5, 2018.)

If you said that the thesis was the entirety of the last paragraph that begins with “Nevertheless, nationwide, there are millions of people...”, then you’re correct! Remember: Sometimes a thesis is more than one sentence, and sometimes it occurs deeper in the essay or article than the first paragraph.

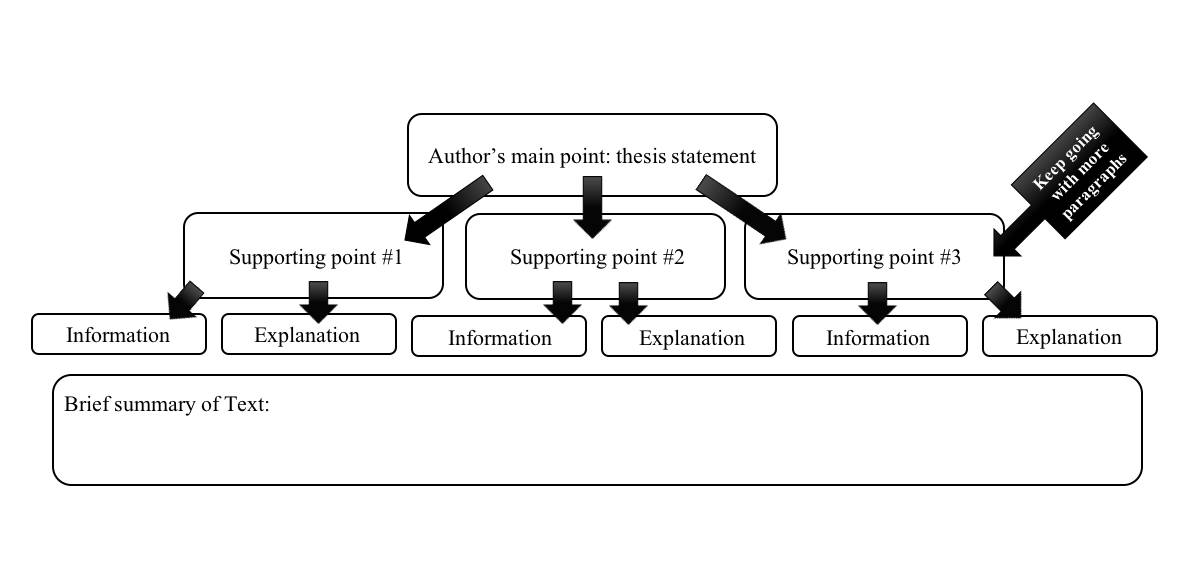

Step 3: Identify the sub-arguments of the text

Next, find the sub-arguments or the supplemental points that support the thesis.

Where might you find these sub-arguments? You may have been taught in previous English classes about topic sentences. In other classes, your teacher may have taught you about PIE paragraphs that contain a Point, Information, and Explanation. Whatever you call it, in academic essays, the first sentence of a body paragraph typically outlines a sub-point that the author wants to make to support the thesis. Think of the topic sentence as a mini thesis statement: It outlines the main point of that paragraph, and that whole paragraph supports the thesis. Everything in that body paragraph comes back to that topic sentence, just as every topic sentence in the essay comes back to the thesis statement. When you map the text in Step 5, you’ll see how these topic sentences are organizationally and visually linked to the thesis.

Step 4: Identify some key details and explanations

Finally, before you diagram your text, you should mark some key details and commentary in the body paragraphs.

Where might you find these? In the body paragraphs of most texts, you should find details such as quotations, facts, statistics, examples, and more. In news articles, especially, you’ll find these in abundance because the writer is trying to offer you all he discovered about a topic. In academic essays and many news articles, you will also find commentary about these details. A good body paragraph—whether it’s your own writing or that of a published journalist—should offer a strong balance between facts and analysis (details and commentary; information and explanation—whatever you might call them).

See if you can identify the topic sentence, details (information), and commentary

(explanation) in the passage below:

...Wealthier, whiter areas also have experienced rising suburban poverty. Montgomery County, among the wealthiest counties in the country, had the region’s largest increase in poverty between 2007 and 2010, when the census showed for the first time that it was no longer majority-white. In Charles County, Md., which has a median family income of $98,560, the poverty rate more than doubled between 2007 and 2015. And according to Elizabeth Kneebone, a researcher at Brookings and the University of California and co-author of “Confronting Suburban Poverty in America,” the jurisdictions that experienced the region’s biggest increases in poverty last decade were farther-flung parts of Virginia, such as Prince William County and Loudoun County—the wealthiest county in America....

(Excerpt taken from Washingtonpost.com, “Poverty is moving to the suburbs. The war on poverty hasn’t followed.,” by Aaron Wiener, April 5, 2018.)

If you said that the topic sentence was the first sentence, good job. The rest are a combination of information and explanation of that information, with anything that is a fact or statistic being a detail.

Step 5: Diagram or map your text

Last, we have the diagram or map. This would be a great strategy for many reading assignments in your English classes or other liberal arts classes, but you can use this technique for chapters in science textbooks, scientific abstracts, and more. Use the chart below for mapping a text.

Page created by H. McMichael