- Las Positas College

- Reading & Writing Center

- Reading Strategies

Reading & Writing Center

Reading to Respond

Reading in an academic setting is quite different than reading for fun, reading to gather information, or reading to socialize--like you might do with "tweets" and text messages. In college, we ask students to take risks when they respond to what they've read. Stretching your mind, broadening your perspective, and seeking to go deeper than just simple comprehension are all goals of reading critically.

Your instructors will most likely ask you to respond to the reading you do in their classes. Reading response can take on all different forms. You might be asked to offer a personal opinion on a current event or connect a reading to a past experience in your life. Perhaps you'll be asked to make connections between two books or texts you've read, and you might even be asked in an English class to put on your critical "lenses"--so to speak--and analyze a text using a literary theory such as the feminist perspective or psychoanalytical literary criticism. Argumentation is another form of textual response, but it's not the kind of "arguing" you might do with your friends or family! Argumentation is about conversation--with yourself, with writers, with critics, and more.

Below you'll find some examples of reading techniques you can use to expand your response skills.

Here are some reading strategies to help with responding to texts:

Close Reading: Reading to Understand, Notice, and Explain

Synthesis: From Parts to a Whole

Text-to-Text, Text-to-Self, and Text-to World

Summarizing

Summarizing means writing a brief description of a text's key points. Summarizing is an excellent way to make sure you understand the main ideas of a text and remember the text later on.

Journaling

Journaling your ideas can help you respond to a text. A double-entry or dialectic journal is perfect for documenting evidence from the text and then responding to that evidence.

- Draw a big "T" on a piece of binder paper so you create a small section at the top for a description of the text you'll be reading and two, equally-sized halves below so you can record your information and responses

- At the top, list the author's name, the text title, and/or relevant page numbers

- On the left, you might record significant quotations from the text, important terms or definitions, or passages that outline something specific, like character development or another topic your instructor has asked you to look for

- On the right, respond to what you've written on the left; your responses might include personal connections, connections to other texts you've read, or connections to the world

A dialectic journal is a great tool to use prior to writing an essay. You can use the left-side information (the quotations or terms) as your evidence in body paragraphs, and the right-side information (your responses) as your analysis or explanation. This pre-writing strategy can help you develop a sound, well-developed body paragraph that is written in PIE format or an 8-point structure in which you integrate outside evidence.

Close Reading: Reading to Understand, Notice, and Explain

When you are assigned to read and truly understand something, often you'll need to practice what is called "multi-pass"reading. This basically boils down to reading a passage more than once, each time practicing a different type of response so you gain a deeper and deeper understanding of the text. This technique is especially helpful when reading fiction, but you can use it with any text.

You’ll read the text three times. First, you’ll read to gather information about main ideas and structure. Second, you’ll read and notice details, figurative language, important vocabulary, and so on. Lastly, you’ll read to understand what the author’s meaning or purpose was in writing this piece. Below are the guidelines you’ll follow each time you read.

Reading #1: Reading to Understand

- What is the title of this piece?

- From the title only, predict what the text is primarily about.

- What is the genre, structure, or type of writing?

- Scan the text and highlight the main point with one color.

- Underline the topic sentences or subpoints with a second color.

- Mark the beginning, middle, and end of this passage.

- In your own words, what is the author’s main point?

Reading #2: Reading to Notice

- Read the text more carefully. Use one color to highlight or underline vocabulary that’s unfamiliar to you. Write three of those here with their definitions.

- Use a ∞ to note connections you have to the text. Write three of those here.

- Use a ! to note strong/interesting words or phrases. You can also note literary devices or figurative language. Write three of those here. What do they say about the author’s intentions?

- Do you notice anything peculiar or interesting about sentence structure? About word choices? About dialogue?

- Use a ? to note questions or confusing parts. Write three of those here.

Reading #3: Reading to Explain

- Read the text once more quickly. Explain, in your own words, what the author’s purpose was in writing this piece.

- Explain what you will take away or what you learned from this text.

- Speak with a partner about the ? comments you made, or, if alone, go back over those ? comments. Can your partner offer clarification or additional explanation? If not, how can you find answers?

- What does this text say that relates to other things you've read about in class?

- Finally, who might you recommend this text to? Why?

Your Turn

Below is a non-fiction passage. See if you can find the answers to the questions above as you read closely:

Paret was a Cuban, a proud club fighter who had become welterweight champion because of his unusual ability to take a punch. His style of fighting was to take three punches to the head in order to give back two. At the end of ten rounds, he would still be bouncing; his opponent would have a headache. But in the last two years, over the fifteen-round fights, he had started to take some bad maulings.

This fight had its turns. Paret knocked Griffith down in the sixth. Griffith had trouble getting up, but made it, came alive and was dominating Paret again before the round was over. Then Paret began to wilt. In the middle of the eighth round, after a clubbing punch had turned his back to Griffith, Paret walked three disgusted steps away, showing his hindquarters. For a champion, he took much too long to turn back around. It was the first hint of weakness Paret had ever shown, and it must have inspired a particular shame, because he fought the rest of the fifth as if he were seeking to demonstrate that he could take more punishment than any man alive.

In the twelfth, Griffith caught him. Paret got trapped in a corner. Trying to duck away, his left arm and his head became tangled on the wrong side of the top rope. Griffith was like a cat ready to rip the life out of a huge boxed rat. He hit him eighteen right hands in a row, an act which took perhaps three or four seconds. I was sitting in the second row of that corner and I was hypnotized. I had never seen one man hit another so hard and so many times. Over the referee’s face came a look of woe as if some spasm had passed its way through him, and then he leaped on Griffith to pull him away. It was the act of a brave man. Griffith was uncontrollable. His trainer leaped into the ring, his manager, his cut man, there were four people holding Griffith, but he was off on an orgy, he had left the Garden, he was back on a hoodlum’s street. If he had been able to break loose from his handlers and the referee, he would have jumped Paret to the floor and whaled on him there.

And Paret? Paret died on his feet. As he took those eighteen punches something happened to everyone who was in psychic range of the event. Some part of his death reached out to us. One felt it hover in the air. He was still standing in the ropes, trapped as he had been before, he gave some little half-smile of regret, as if he were saying, “I didn’t know I was going to die just yet,” and then, his head leaning back but still erect, his death came to breathe about him. He began to pass away. As he passed, so his limbs descended beneath him, and he sank slowly to the floor. He went down more slowly than any fighter had ever gone down, he went down like a large ship which turns on end and slides second by second into its grave. As he went down, the sound of Griffith’s punches echoed in the mind like a heavy ax in the distance chopping into a wet log.

(Excerpt taken from "The Death of Benny Paret" by Norman Mailer)

Hopefully you noticed that Mailer used run-ons and short, choppy sentences in this retelling of the death of Benny Paret at the hand of Emile Griffith. Why might this author purposely use run-ons--especially when English teachers tell you not to do that?!

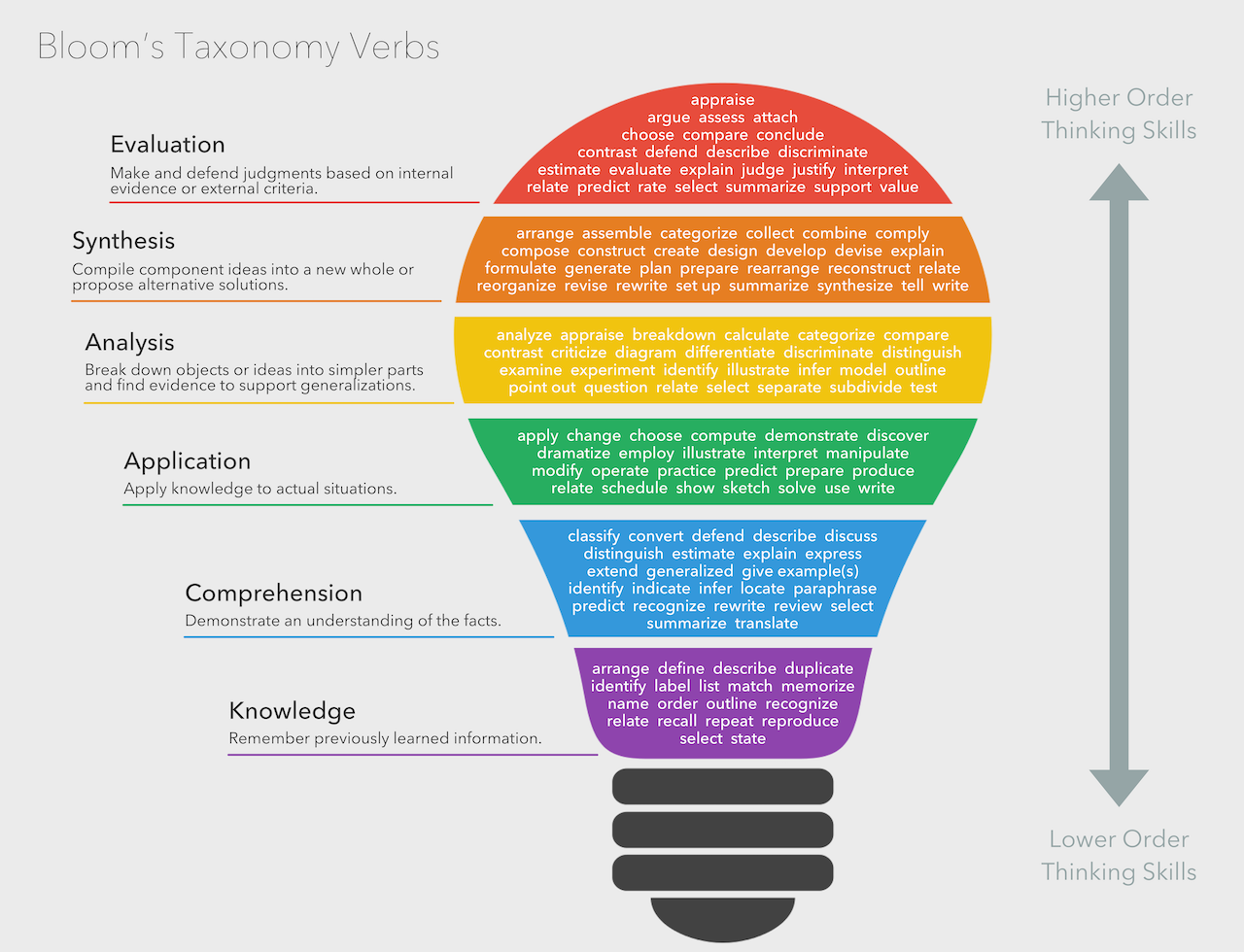

Synthesis: From Parts to a Whole

If you consult Bloom's Taxonomy of learning domains, you will see that at the top of the chain--almost at the very top of the higher order thinking skills--is something called synthesis. Synthesis, in its simplest form, is creating a whole out of parts. In an English class, you can use a variety of sources and other authors' ideas combined with your own ideas or those of other critics to craft a "whole" or broader thesis. This is synthesis!

You might be asked to write a synthesis essay in one of your English classes. If you are, here are some steps you can take to "synthesize" information from your sources before you embark on writing the first draft.

Step 1: What is the Essay Prompt Asking?

Know what your essay prompt is asking you to discuss. Maybe the essay prompt asks you to analyze the relationship between two things, such as race and poverty. In this case, you'd be researching sources that discuss race, some that discuss poverty, but also those that discuss the interrelatedness of both of those topics. Before you begin investigating resources to use in your paper, you should understand the prompt.

Step 2: Establish Your (PRELIMINARY) Position

Do you have a personal opinion about the essay topic? Likely you do, and that can act as a guide when you research. If you are writing a research paper, perhaps you turn the prompt into a research question before embarking on your research. If you are discussing the connection between race and poverty, you most likely have a hunch that one relates to the other--but how? It’s vital at this point for you to keep an open mind since a more mature, stronger essay will evolve if you’ve considered all sides and resisted the urge to oversimplify your argument. The best essays will be the ones in which the writer has given consideration to the nuances and complexities of the topic.

Step 3: Choose and Read Your Evidence

Choose your evidence and read through it carefully, annotating all texts so you can use them when you write your essay. When choosing texts, make sure you have a good idea about what your thesis will be so you can wisely select your readings. Better yet, selecting texts might be an organic process: Read some articles, digest their main points, think through a thesis, read some more articles, revise your thesis, etc. Be careful when you choose your evidence. The sources you choose will make or break your argument. For instance, have you ever argued with someone about which sports team was better? If so, you know that just offering vague, generalized opinions won’t get you anywhere. You need to recount certain plays, know player stats, be able to recount particular games to prove your point that the team you love most is, indeed, the best team out there. Do the same with the articles you choose. Know what the main point is, what the subpoints are, what examples the author uses to make his/her point, and so on.

Step 4: Analyze Your Evidence and Evaluate It for Reliability, Validity, and Currency: THE CRAAP TEST

Use the CRAAP test to evaluate your sources, or, at the very least, analyze the argument each source is making: What claim is the source making about the issue? What data or evidence does the source offer in support of that claim? What are the assumptions or beliefs (explicit or unspoken) that warrant using this evidence or data to support the claim? Consider such things as when a source was published. What was this source’s original purpose (to entertain? to inform? to convince?)? Even seemingly unnecessary things like the gender or the biography of a particular author can be important to your thesis.

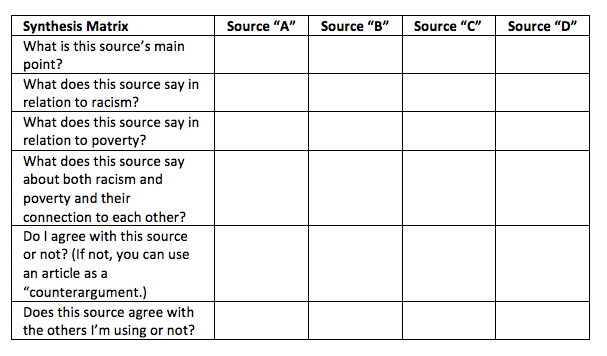

Step 5: Consider Your Conversation

Who are the participants in this conversation? Do you agree or disagree with each? What does each have to say about poverty...or race...or both? Create an imaginary conversation and allow each writer's voice to contribute to your argument and help you make your point. Strangely enough, you might have to use a source that you disagree with in order to prove a point. Use the sample chart below, or one like it, to figure out what each "part" is saying that will help you create your "whole" argument.

Step 6: Begin Your Outline by Developing a Working Thesis

Step 6: Begin Your Outline by Developing a Working Thesis

Here is where you refine what you want to say by drafting a solid, well-developed thesis statement that encompasses what you plan to prove. This is your central proposition, and it drives the essay forward. Keep coming back to this thesis time and time again. With every new paragraph, come back to this thesis. When you are halfway through writing your essay, come back to your thesis. When you’re finished, go back to your thesis to ensure you’ve supported it, argued it well. You should offer your thesis early in the essay.

Step 7: Outline Your Position by Using Evidence and Explanation

Build your argument by using sources to state your case. Incorporate all these conversation participants. You can use language like you might in an argumentative essay: “Source A takes a position similar to mine” or “While I disagree with Source C when he says that…”. Each body paragraph should offer a subpoint that supports your thesis. Here are some dos and don'ts for synthesis papers:

DO:

- Use more than one source in each body paragraph to build that important source "conversation" and show how the "parts" make a "whole" argument

- Offer short lead-ins or signal phrases to quotations instead of giving detailed background information on each source

- Make sure you use ALL sources listed on your Works Cited page

- Always identify your sources so the reader can keep the "conversation" straight in his or her head

DON'T:

- Use extensive chunks of summary; synthesis is different than summary

- Start body paragraphs with quotations

- Bombard your reader with all sorts of long quotations without stopping to paraphrase and then explain and examine those quotations

- Forget to think of yourself and your own views as part of the conversation

Step 8: If required, write your synthesis essay according to your instructor's requirements

Text-to-Text, Text-to-Self, Text-to-World

Responding to literature and other written works is sometimes as simple as making connections. You can make personal connections (text-to-self), connections to other works you've read (text-to-text), and connections to things that are happening around you or throughout history (text-to-world).

If you are an instructor looking for ways to engage your students with connections in the classroom, check out this New York Times article by Katherine Schulten titled "Making It Relevant: Helping Students Connect Their Studies to the World Today."

If you are a student looking for ways to connect to a text in front of you, follow the steps below.

Step 1: Text-to-Self

- What does this text remind me of in my life?

- What do I have in common with this text?

- How does this text offer different ideas than those I have?

- Has something like this ever happened to me?

- How does this relate to my life?

- Have I changed my thinking or ideas after reading this text?

- What did I learn, and how did that differ from what I already knew?

- What does this remind me of?

Step 2: Text-to-Text

- Have I read anything about this topic before?

- What other books or texts does this remind me of?

- What am I learning in other classes or textbooks that relates to this text?

- How is this text the same or different from what I've read before?

Step 3: Text-to-World

- What does this remind me of in the real world?

- What historical examples or current events does this text connect to?

- What is going on in politics right now that connects to this text?

- Have I traveled somewhere that connects to this text?

- How is this the same or different from what happens in the real world?

Your Turn

Below is a non-fiction passage. See if you can find the answers to the questions above as you read closely and connect the text to yourself, to other texts you've read, and to the world around you:

After sunset…I walked out into the desert…Light was thinning; the scrub’s dry savory odors were sweet on the cooler air. In this, the first moment for a walk after long blazing hours, I thought I was the only thing abroad. Abruptly I stopped short.

The other lay rigid, as suddenly arrested, his body undulant; the head was not drawn back to strike, but was merely turned a little to watch what I would do. It was a rattlesnake—and knew it. I mean that where a six-foot blacksnake thick as my wrist, capable of long-range attack and armed with powerful fangs, will flee at sight of a man, the rattler felt no necessity of getting out of anybody’s path. He held his ground in calm watchfulness; he was not even rattling yet, much less was he coiled; he was waiting for me to show my intentions.

My first instinct was to let him go his way and I would go mine, and with this he would have been well content. I have never killed an animal I was not obliged to kill; the sport in taking life is a satisfaction I can’t feel. But I reflected that there were children, dogs, horses at the ranch, as well as men and women lightly shod; my duty, plainly, was to kill the snake. I went back to the ranch house, got a hoe, and returned.

The rattler had not moved; he lay there like a live wire. But he saw the hoe. Now indeed his tail twitched, the little tocsin sounded; he drew back his head and I raised my weapon. Quicker than I could strike, he shot into a dense bush and set up his rattling. He shook and shook his fair but furious signal, quite sportingly warning me that I had made an unprovoked attack, attempted to take his life, and that if I persisted he would have no choice but to take mine if he could. I listened for a minute to this little song of death. It was not ugly, though it was ominous. It said that life was dear, and would be dearly sold. And I reached into the paper-bag bush with my hoe and, hacking about, soon dragged him out of it with his back broken.

He struck passionately once more at the hoe; but a moment later his neck was broken, and he was soon dead. Technically, that is; he was still twitching, and when I picked him up by the tail, some consequent jar, some mechanical reflex made his jaws gape and snap once more—proving that a dead snake may still bite. There was blood in his mouth and poison dripping from his fangs; it was all a nasty sight, pitiful now that it was done.

I did not cut off the rattles for a trophy; I let him drop into the close green guardianship of the paper-bag bush. Then for a moment I could see him as I might have let him go, sinuous and self-respecting in departure over the twilit sands.

(Excerpt taken from "The Rattler," in The Road of a Naturalist, by Donald C. Peattie)

Page created by H. McMichael