- Las Positas College

- Reading & Writing Center

- Reading Strategies

Reading & Writing Center

Reading to Understand

One of the most common reasons for reading in college is to understand information. You might read for comprehension before taking a test in your biology class; you might read to understand an article before you write an essay in your English class. It's important that you have a strong selection of reading strategies for reading comprehension since understanding what you've read is the foundation for good writing...and good learning.

These strategies are especially helpful if your purpose is...

- To contribute to class discussions

- To perform well on quizzes and tests that evaluate your comprehension

- To write summaries and essays

- To conduct experiments and do well in classrooms that involve labs

- To recall information at a later date

Here are some reading strategies to help with understanding:

SPA: Skim/Scan, Predict, Ask Questions

KWL: What Do I Know? What Do I Want to Know? What Did I Learn?

SPA: Skim/Scan, Predict, Ask Questions

(Before Your Reading)

S = Skim/S = Scan

- Skimming is when you look for the main ideas of a text by reading quickly

- Identify the thesis and main points

- Look at the first sentences of each paragraph--the topic sentences

- Pinpoint a few sub-arguments

- Scanning is when you look up and down the page quickly, looking for important details

or specific information

- Search for key phrases

- Look for facts and statistics

- Pay attention to other details like titles, bold type or italicized words, photograph captions, or author names and credentials

P = Predict

- Make a guess as to what the reading will be about

- Make a guess as to what the author's main point is

A = Ask Questions

- What do you think you will learn from this reading?

- What do you want to learn?

- What information will you be required to know after reading this text?

- Who or what is this text about?

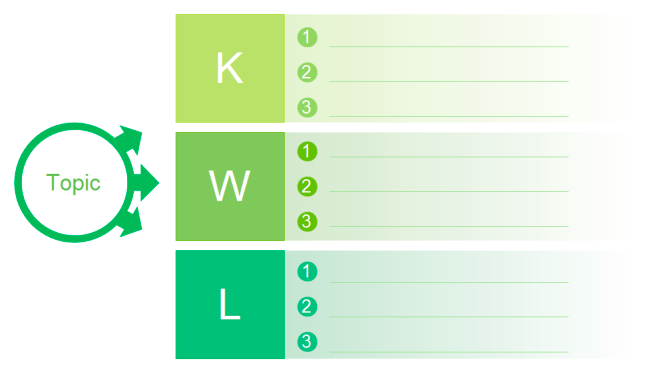

KWL: What Do I Know? What Do I Want to Know? What Did I Learn?

(Before and During Your Reading)

Before you begin, you might consider printing out a chart or making one of your own. Click the KWL Chart image above to go to a printable chart.

What Do I Know?

Before you begin reading a text, first think about what you already know about a topic. Do a quick skim/scan through the text and ask yourself these questions:

- What prior knowledge do I have about this subject?

- How long will the reading be?

- How much time is required to read this text?

- What type of text is this?

- Who is the author? What is the source?

What Do I Want to Know?

Next, think about what you want to know after reading this text and ask yourself these questions:

- Do you need to know something specific about this text in order to pass a test or write an essay?

- Do you need to know certain details or facts from the text?

- Do you need to evaluate the text for reliability?

- Are you just intrigued by the topic and want to know more?

Now Read!

- While you read, annotate or read actively by taking notes and using some of the critical reading tips above.

What Did I Learn?

- Finally, think about what you learned from this text and ask yourself the following questions:

- What did you learn that was new to you?

- What did you learn that reinforced something you already knew?

- What questions arose during your reading?

- What information could possibly be asked on a test? Be used in a research paper?

Annotating a Text

(During Your Reading)

What Is Annotation?

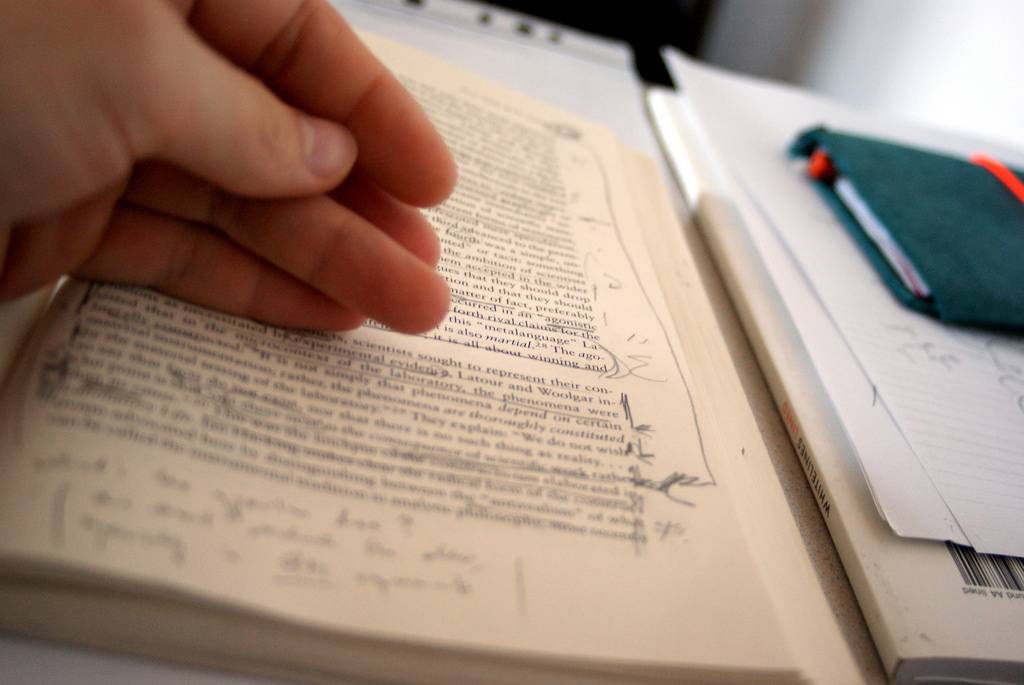

Simply defined, an annotation is a note or comment. The act of annotating a text is making comments in the margins of your reading. What lines you choose to annotate, and what comments you choose to make will often depend on the purpose you have for reading the text.

Your purposes for reading a text in an academic setting might include learning about a topic, preparing for tests, and preparing to write a paper—in addition to personal growth and enjoyment.

Underlining in Combination with Annotation

Underlining words or sentences helps you identify important sections to return to later. However, it’s difficult to remember the reason you underlined a part of the text when you skim through the reading a second time. Annotation will help you identify different types of lines that suit different purposes. It will also help you engage in active reading.

Annotation and Active Reading

When you annotate a text, you start a dialogue with the author. You might be asking a question in the margins: “What are you saying?” or “Where is your proof?” You might be responding with your own experiences: “So true!” or “My friends, too!” Your interaction with the text helps you pay more attention to the reading and adds your own perspective. You are actively considering the meaning of the text and its implications. This active reading will not only help you understand a text, but it will help you generate your own ideas.

Strong, Hard, and Weak Lines

While you're reading, you might not have time to write long annotations in the margins. Instead, you can make quick annotations to review later. Use the following shorthand to help you identify lines that are important, difficult, or unconvincing: Strong Lines (!) Hard Lines (?) Weak Lines (X).

- Strong Lines (!): In the margin of your text, write an exclamation point next to any important, well-written, or interesting lines that illuminate the ideas or fulfill one of your purposes for reading. This might also apply to lines that remind you of personal experiences or personal knowledge. It’s sometimes helpful to have a little more information to remind you why you considered a line “strong.” Here are some example annotations with additional information: Me too! Good Pt! Wow! Love this! Quote! Main idea! Beautiful!

- Hard Lines (?): These are lines that are difficult to understand. Try re-reading them, and if you still have trouble, write a question mark next to them in the margin. Then move on. When you're done with the chapter, go back to the hard lines and try to figure them out. You might also use your class’s online posting area to discuss the meaning of such lines, or bring them up in an in-class discussion. Finding out what these lines mean and how to get meaning from them will improve your reading ability. Often, the most important ideas in a text are the hardest to understand because they present new concepts or sophisticated ideas. In other cases, you might simply need to look up a vocabulary word. Here are a few example “hard line” annotations: Vocab.? Huh? Who said this? Who cares? Yikes?

- Weak Lines (X): Use an "X" next to lines that are not true to your life experience or knowledge or a concept that you would like to challenge. It's a good idea to use one or two words that remind you of what differs in your experience, like "X, Jennifer and Matt," which means remember how Jennifer and Matt’s example differs from what the text says. Here are some other examples: Not true X No proof X Not me X Really X What about Congress (or some information that’s excluded by the author) X

- Customize: You might choose a custom shorthand to meet your own reading needs. For example, imagine you know that you will need to write about the psychological insights made by the author throughout the book; you might choose to write PSY every time you read a psychological insight. Sometimes, you discover your purpose for reading while you are reading—you discover a topic that interests you, such as symbolism, and you create your own short-hand at that time, like SYMB. You could also put an asterisk in the top corner of every page that has a line you might use so that you can skim through the book more quickly.

A thoughtful or inspired reader might write more in a journal after the reading, referring to annotated lines.

Adapted from Las Positas College’s “Reading Strategies Student Handouts English 104-105”

Vocabulary Development

(During and After Your Reading)

Sometimes when you buy a used college textbook from the bookstore, you’ll see entire chapters color-coded by bright highlighters. However, highlighters aren’t all they’re cracked up to be, and if you rely on someone else’s notes, you’re missing the whole point of note-taking. It’s better to use a pen since you can focus your note-taking on what you want to learn from a text or what your main purpose might be.

A text might be difficult for you, especially if the language is complex. Understanding what the words mean in a text is imperative for understanding the text as a whole. If you’re unable to use context clues to understand difficult words, you can keep track of the words in many ways. One of the not-so-great ways to understand vocabulary is to pause midstream with your reading and look up the word in the dictionary. That might be a strategy you learned in elementary school, but stopping to look up words will inhibit your reading comprehension. Better to save the word discovery for later, or when you skim/scan the text on the first go-round, you can jot down words you aren't familiar with and start with finding the definitions before you begin reading.

Annotate and keep track of any unfamiliar words:

- First, decide how you want to keep track of words you don’t understand. You could start a list on a piece of paper, circle or highlight vocabulary words, or write the words in the margins of your book

When you have your list from a certain section of text, you can dig in deeper to find out the meaning:

- Look up the words in your dictionary

- Use context clues (the words around your word) to figure out the meaning

- Look later in the passage to see if the author uses illustrative words to explain your word

- Be logical and think about the etymology or word’s construction (e.g. if you don’t know what “subordination” means, think about only half of the word: “sub-” is a prefix that has to do with being under something, like a submarine; “ordination” has to do with order; therefore, “subordination” means one thing being under another)

Build your vocabulary by being proactive about its development:

- Keep a list of words that you learn the definitions of

- Play word games on your phone/computer or use an app to receive notifications with a “Word of the Day”

- Read often and across genres because research shows that strong readers have the best vocabularies and vice-versa

- Use mnemonic devices (e.g. FANBOYS to remember the seven coordinating conjunctions)

- Use word association to create visual images of words (e.g. to remember a word like “subordination,” imagine a submarine positioned below the water's surface; enlarge that image in your mind and repeat it multiple times until it sticks)

- Read for fun because the more words your brain sees, the broader your vocabulary

Here are a few of the common words to pay attention to along with their meanings:

Remember that understanding the words an author uses doesn’t only involve complicated or unknown words. You can use words that are common and repeated to better understand a text; it’s just a matter of noticing them and knowing why the author used them. Sometimes the most helpful words are the prepositions and conjunctions that guide your mind along the pathways of the author’s ideas. Master these words and phrases and you will almost immediately become a better reader.

- additive words: also, further, moreover, in addition, too, and, besides, etc.

- alternative words: either/or, neither/nor, other than, otherwise, etc.

- amplification words: for example, specifically, as, for instance, such as, like, e.g., etc.

- cause and effect words: since, then, because, so, thus, consequently, etc.

- concession words: granted that, of course, although, etc.

- contrast and change words: but, on the contrary, still, conversely, on the other hand, although, despite, etc.

- emphasizing words: above all, more importantly, indeed, etc.

- equivalent words: as well as, at the same time, similarly, equally important, likewise, etc.

- order words: first, second, last, next, etc.

- qualifying words: if, although, unless, providing, whenever, etc.

- repetitive words: again, in other words, to repeat, etc.

- summarizing words: for these reasons, to sum up, in conclusion, briefly, etc.

- time words: afterwards, before, meanwhile, subsequently, presently, formerly, previously, etc.

Page created by H. McMichael

Some ideas adapted from the Las Positas College’s “Reading Strategies Student Handouts English 104-105”; some ideas adapted from Dartmouth College's Reading Strategies Website